Lean management has evolved greatly since the days of Henry Ford. Here’s what you need to know about Toyota, the 8 wastes, customer value and more.

Written by: Nigel Richardson

Rather than replicate at length the abundance of content on the history of Lean management, what this firstly seeks to do is offer you a summary of the timeline of its development and sign post more information.

Perhaps more important is the section in which I address the importance of value, waste and flow in Lean lexicon, as without this foundation your application of this improvement methodology will likely falter.

I have been fortunate enough to apply my experience across a variety of industries including Pharma, Aviation, Supply Chain, Outsourcing, Retail, Start-ups, and Government.

Within those areas I have encountered a broad spectrum of prior experience on this topic.

Ensuring you and the business you are working with have a great understanding of the above three principles and leveraging the simplest way to pursue these principles for the business problem you face, is the main foundations to success.

What is Lean Six Sigma?

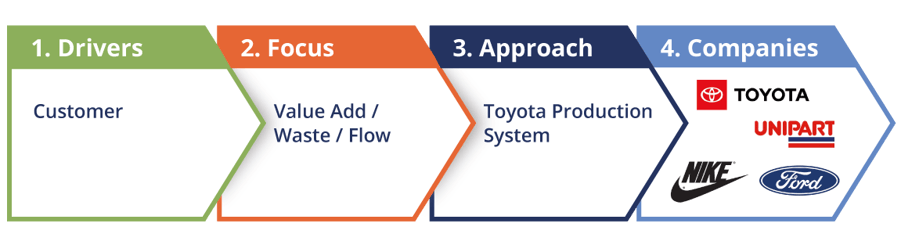

As continuous improvement has grown in popularity, so too debate over the effectiveness of Lean and Six Sigma approaches. Lean’s focus is eliminating waste and creating flow in process, whereas Six Sigma techniques focus on defects.

The reality is that both come down to delivering what is the best value for customers.

However, the differences between the two may not be so clear. In which case, this comparison table spells this out:

| Lean | Six Sigma | |

| Driving principle | Customer value | Consistency in process and results |

| Focus | Create flow and eliminate waste | Create standardization and eliminate variation |

| Key frameworks | 7 waste (now the 8 wastes) | DMAIC projects |

| Example adoptors |

Toyota Unipart |

GE Motorola |

| Delivery methods | Continuous improvements | Scoped projects |

When considering the “first principles” above., there exists a distinction in the mindset of each method that does set them apart and is important to understand.

However, both methods are focused on “making the business better” and it is common for companies to combine principles and tools from each of these methods into an overall improvement approach.

The following are examples of how that can happen:

1) Deploying a Lean improvement that is large and complex (e.g. Value Stream Level) which therefor runs with a level of DMAIC structure for each project phase

2) Having a very well defined measurement system for any form of improvement that can make use of data collection and statistical interpretation techniques frequently used in Six Sigma

3) Relying on some of the Lean interventions such as Kanban and 5S to drive standard work that will explicitly reduce variation in process for a Six Sigma motivated improvement.

The history of Lean

The history of Lean is well-documented, but can be summarized in 5 eras:

1. Lean inception (1900-1920)

- Henry Ford’s Model T sparks the mass-production era of manufacturing, where continuous flow takes its roots

-

Kiichiro Toyoda visits and observes a US textile factory, and sought to improve his own manufacturing process

2. Competition sparks (1920-1938)

- Ford and General Motors lead the way and dominate global automobile markets, including Toyoda’s homeland of Japan

- Toyota Motors is founded, with Toyoda laying out factories based on a plan which is optimized for early flow production

3. Wartime woes (1939-1945)

- With the world embroiled in the devastation of war, rationing of supplies and increased demand gives cause for more effective, innovative, and resourceful manufacturing

- The likes of Ford and Toyota answer the call for military manufacturers in this period, with a heightened focus on shortened time to deliver

4. Post-war growth (1945-1970)

- In the wake of the Second World War, Toyota and Ford collaborate to use their newfound knowledge, with key directors from each corporation working together in the face of limited material, labor and capital

- 1954 sees the rise of the just in time manufacturing system with Toyota’s supermarket system of supplying parts inspired by a founding father of Lean, Taichii Ohno, adapting his learnings from the US, establishing what we now know as the Toyota Production System

5. The great enlightenment (1970 onward)

- 1979 saw Norman Bodek document and translate Toyota’s teachings on Lean, leading to manufacturers and researchers on a mass scale seeking to adapt the theory and best practices beyond the automotive industry

- NBC’s 1980 documentary ‘If Japan Can... Why Can't We?’ highlighted the work of William Edwards Deming, and served to inspire a slumping US economy

- James Womack releases his ‘The Machine that Changed the World’ in 1990, a seminal peace in Lean literature

- ‘The Toyota Way’ is published in 2011, Jeffrey Liker’s comprehensive overview of how Toyota embedded Continuous Improvement into their organization and inspired generations

Toyota's influence on Lean

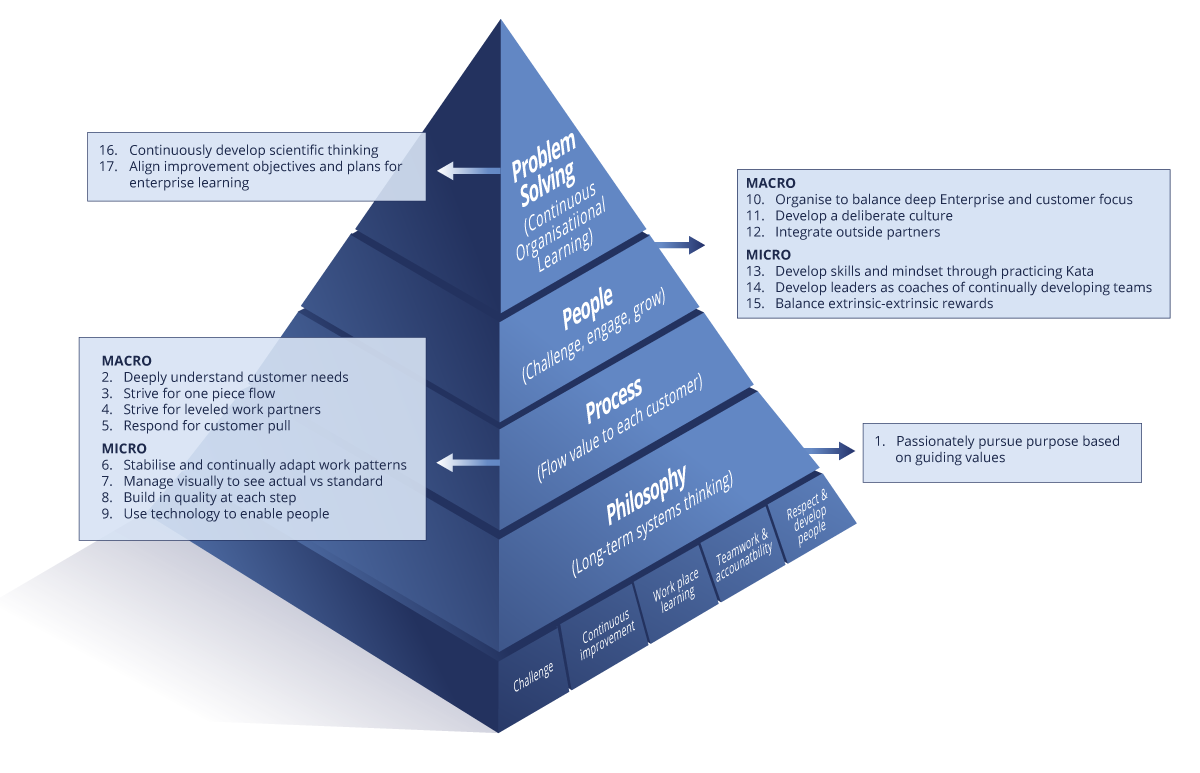

Synonymous with Lean thinking is Toyota, specifically the Toyota Production System. The graphic below captures the key aspects of Toyota and Lean.

The 4Ps model

In his book ‘The Toyota Way’, Jeffrey Liker gives a comprehensive overview of how Toyota embedded Continuous Improvement across their organization through the rigorous application of 14 principles outline below.

They are grouped into what is often referred to as the 4Ps model:

*Source ‘The Toyota Way’ Jeffrey Liker

The legacy of the Toyota Prodution System

Toyota created a comprehensive operating framework for their manufacturing operations referred to as the Toyota Production System which Liker also outlines in his book.

It is this integrated system that many companies over the years have looked to replicate to varying levels of success.

The success is mostly attributed to how well these companies invested in driving the 14 principles as a cultural norm above and beyond providing the toolbox for improvement to happen.

I would thoroughly recommend The Toyota Way, 2004 Jeffrey Liker for those wishing to really delve into this topic further.

The core principle of Lean - customer value

The essence of Lean lies with understanding what parts of your business and process directly contribute to customer value:

1) Value added

-

- These activities directly contribute to what the customer is prepared to pay for.

- It would be very difficult to justify to a customer to pay for a loaf of bread if it failed to go through the oven stage of the process and was just dough in a bag. The act of baking in the oven is an essential step to providing a product that the customer wants to buy.

2) Non-value add

-

- These activities play no role in the value of the end product in the eyes of the customer.

- For example, the baker may spend time (and energy) taking dough that has proved from one part of the build to another where the oven is. If you as a customer had to pay more for your bread because of this extra cost, I am sure you would object.

3) Non-value add but necessary or essential non-value add

-

- Finally, we have activities that have no impact on the end product but are actually important for other reasons.

- For example, the baker may spend time cleaning and inspecting the equipment in line with cleanliness and health and safety regulations. This is still necessary to protect the baker’s “license to operate”.

The 8 wastes of Lean

In the eyes of a Lean organization, non-value-added activity can be defined as a type of waste.

Once you understand the 8 wastes, they become easy to spot in everyday life:

- Defects – Providing the wrong product or a failure in customer journey

- Overproduction – Providing more than is needed by the customer

- Transport – Your product or material having to be moved from place to place

- Waiting – Your product (or customer) having to wait periods of time as it moves through the process

- Inventory – Large volumes of product (or customers) stuck between various stages of the process

- Motion – Your staff having to move excessive distances to fulfil the task at hand

- Processing – Your product (or customer) being subject to process steps that just aren’t needed

- Skills – Your staff’s ability to add maximum value is limited by a many basic tasks

The principle of flow

The principle of flow is critical to understanding the Lean organization mentality.

Imagine your product as a river.

The product should flow, like this river does, efficiently downstream as it grows in size and strength with various additional components being added as it passes various tributaries.

The flow of the river is set by the gradient the water has to flow down, and for this magical river the rate of flow is exactly the same as the rate at which the water downstream is being consumed through demand from the city and agriculture.

The river also runs in a straight line with no deviations to divert it from its fastest route to the market it feeds.

This is the principle of flow.

Achieving single piece flow

The fundamental challenge Lean organizations set is that of ‘Single Piece Flow’, which can be explained as:

How would we set up out facility and processes to be able to continually process our products as individual items (not in batches), following an uninterrupted flow from raw materials to finished product being with the customer?

This fundamental principle is what gives operations the flexibility to adapt to commercial challenges and customer choice.

Now, one could argue many reasons why my example is unrealistic.

An obvious challenge would be dams.

Dams provide a practical solution to the reality that the flow rate of a river cannot be regulated, in nature the input (rain) varies and the demand downstream also varies.

The result is a need to introduce some water inventory at various points in the river’s supply chain to scope with scarcity of supply of rain or surges in demand.

Balancing this first principle mindset with the pragmatic reality you face is one of the delicate sciences Lean organizations continually experiment with.

Looking beyond Lean

While Lean’s place in continuous improvement is undoubted, and will feature in future blogs, I would be remiss to not mention the other key player in continuous improvement – Six Sigma.

With Toyota and Ford playing a key role in the growth of Lean, it is the likes of General Electric and Motorola who have championed Six Sigma, and our overview of the school of thought is required reading for anyone interested in the field of continuous improvement

Continue learning about continuous improvement

Click here to learn more about continuous improvement, or take a look at these content recommendations:

- Continuous improvement in 2020 and beyond: Watch how continuous improvement will evolve into the 2020s and how you can be successful.

- DMAIC v Six Sigma v Lean: Our guide to the steps and tools you'll need when driving process improvement through one of these three methodologies.

- The Leader's Guide to Continuous Improvement: Download this eBook to get a comprehensive overview of how DMAIC, Six Sigma, Lean, PDCA can support your business in finding competitive advantage.

About the author

Nigel Richardson is a continuous improvement expert. His background spans 20 years in business transformation and continuous improvement across retail, pharma, aviation and IT supply chain. He is passionate about supporting organizations to achieve their strategic, transformational and improvement goals, and outperform their peers year after year.

If you’d like to talk more about your strategic challenges, reach out to him on nigel.richardson@i-nexus.com or connect with Nigel on LinkedIn for the latest Strategy Execution insights.